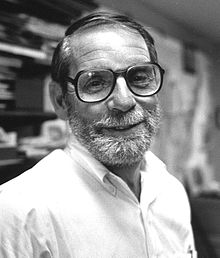

This is exactly the strategy John McPhee employs in his book, Basin and Range. McPhee is a writer interested in everything: the Merchant Marine, Russian Art, the Swiss Army, the cultivation of oranges, the building of birch bark canoes, the collection and consumption of road kills. Yet he doesn’t assume a similar level of interest from his readers. Instead he courts them by seeking colorful individuals through whom he tells the story and so entices readers into the subject. In Basin and Range, he chose the geologist Kenneth Deffeyes.

“Deffeyes is a big man with a tenured waistline. His hair flies behind him like Ludwig van Beethhoven’s. He lectures in sneakers. His voice is syllabic, elocutionary, operatic. He has been described by a colleague as ‘an intellectual roving shortstop, with more ideas per square meter than anyone else in the department–they just tumble out.’”

McPhee’s quick character sketch provides readers with a glimpse of the energetic, idiosyncratic geologist, the kind of man who should prove a worthy guide to the narrative. McPhee selected Deffeyes as the central character for his personality and familiarity with the Great Basin. The geologist serves as the entry point into the subject. Though him, general readers learn to care about such arcane subjects continental drift, subduction zones and seafloor spreading. They might never crack the cover of a geology textbook, but once they get to know Deffeyes, chances are, they’ll be hooked.

The use of characterization in Basin and Range is typical of narrative nonfiction or fiction. Deffeyes’ character is the lynchpin of the story, the engine of the narrative. In the course of the book, readers learn a lot about geology, but they do it through him. Knowledge is imparted through a person, not presented in a dry, abstract manner.

Writers like McPhee adopt this strategy for a very simple reason: Readers identify with people. If writers find a sympathetic, interesting character, readers will follow them anywhere, even through the twisting explanations of synclines and anticlines. As Philip Gerard points out in Creative Nonfiction, “One way or another, the focus of every really good story is a person.”

My spring Seattle writing class will address characterization as well as other techniques of narrative writing. See the course description on Seattle writing classes page.

The Writer's Workshop

The Writer's Workshop