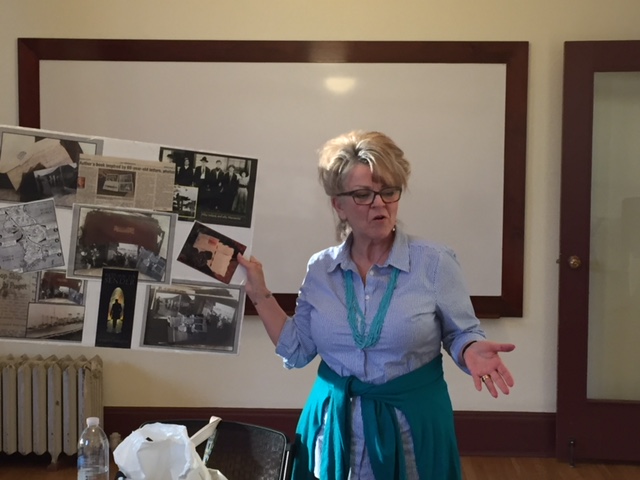

In my Seattle writing classes, I teach how to write a dramatic scene, an especially effective way of organizing stories. In my Seattle writing classes, I explain how to use dramatic scenes to give life and movement to stories, whether fiction on nonfiction. It’s a technique that also helps you as a writer organize the story. You don’t need to go into detail about everything, but rather just the key moments that made the trip memorable.

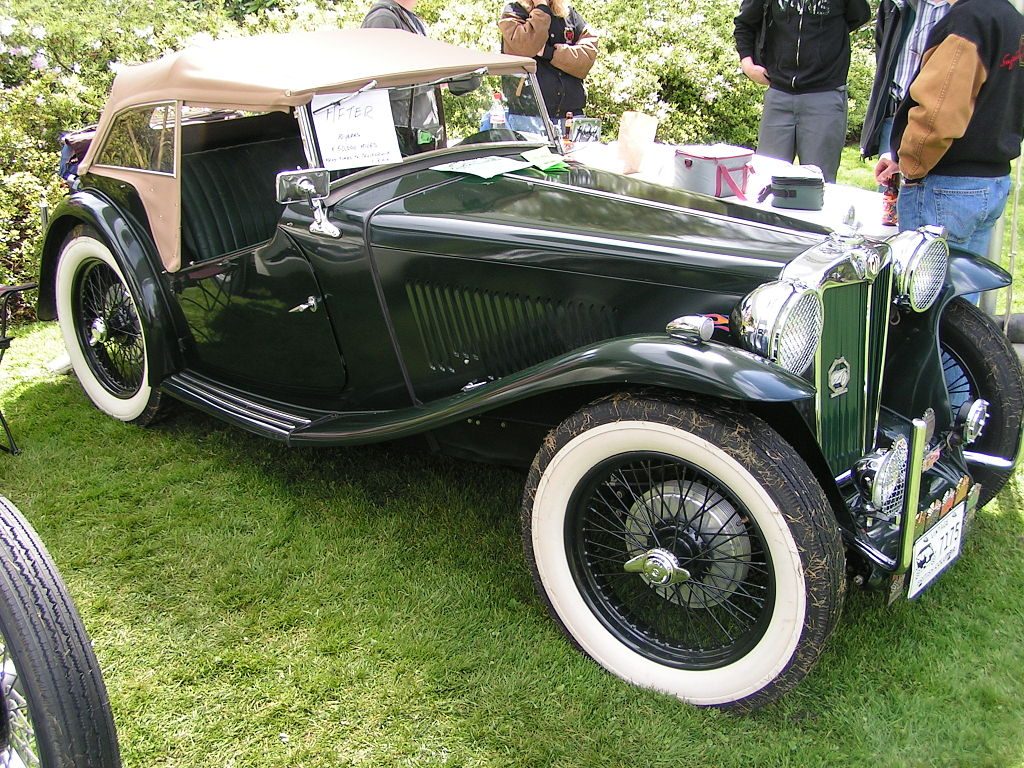

On a recent trip to England, I used dramatic scene to highlight some of the adventures of the trip. Although travel stories tend to highlight the pleasures of a trip, I also like to write about the challenges and inconveniences. One of the biggest challenges was driving on the LEFT side of the road, with a clutch in my left hand. The whole operation was widely counter intuitive, with lots of honking drivers, speeding motorcyclists and phone-distracted pedestrians thrown into the mix.

As I tell students in my Seattle writing classes, it’s a good idea to always take a notebook with you to record your adventures. I took a reporter’s notebook and filled it with impressions of the trip, especially those involving driving. The hardest part was rewiring my brain to go left, not right, at key moments. This wasn’t so hard on a straightaway, but devilishly difficult on a roundabout. I followed the car in front of me, said a prayer, and plunged through it, occasionally earning a honk or other gesture.

It was a great pleasure to return the rental car to Heathrow airport and have someone else drive into London. Once there, we took the Tube and buses around, very convenient, but not the great material I found through driving on the wrong side of the road.

For more on writing with dramatic scenes, please sign up for my winter Seattle Writing class, The Arc of the Story.

The Writer's Workshop

The Writer's Workshop