THE WRITING LIFE WITH THE WRITER’S WORKSHOP

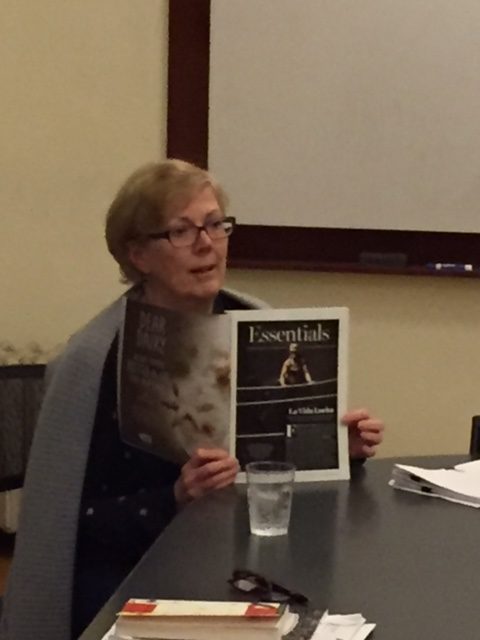

In her essay collection, Mystery and Manners, Flannery O’Connor talks about writing as a habit of art. I discuss this approach in The Writer’s Workshop talk on The Writing Life, on Wednesday, Oct. 11 at 7 p.m. in room 221 at the Good Shepherd Center in Seattle’s Wallingford neighborhood. This approach emphasizes that writing is a craft and a daily discipline as well as an art. It relies as much on regular practice as inspiration. While inspiration plays a large part in any literary breakthrough, the habit of art gives concrete expression to inspiration, making the story or book possible. Here are some of thoughts on how to develop your own habit of art.

WRITING AS A PROCESS – Thinking of writing as a process allows you to complete a story in a series of steps, avoiding the paralysis of perfectionism. Instead, write a draft (a “shitty first draft” in Anne Lamott’s memorable phrase), organize and polish it. By breaking things down into a series of steps you increase the odds of creating something special.

SET A SCHEDULE – Set up a time to write, ideally five days a week for an hour or so a day. If possible, write for more than that. It takes practice to hone and perfect your craft. This comes by repetition. I usually write about three hours a day, five days a week, sometimes more, sometimes a little less. I schedule the time and try to stick to it.

SHORT ASSIGNMENTS – As the Chinese say, the thousand mile journey begins with the first step. Give yourself short assignments every day – a page, a lead, a character sketch. Then perhaps complete a story or novel chapter every week or so. Making steady progress increases your confidence and the fluency of your writing.

I’ll be offering a free class, The Writing Life, on Wednesday, Oct. 11 at 7 p.m. in room 221 at the Good Shepherd Center in Seattle’s Wallingford neighborhood. You’ll have a chance to learn how to get started with your story, hear about our classes and enjoy some delicious Provençal food and drink. Please RSVP.

The Writer's Workshop

The Writer's Workshop