Here are images for the next issue.

The Writer's Workshop

The Writer's Workshop

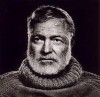

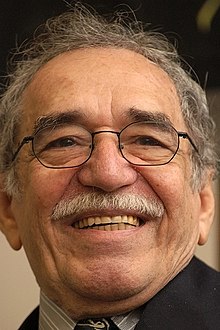

These are vivid word pictures that introduce a character and bring them to life on the page, as Mark Twain does in his stories and books. The character sketch should be short, vivid, succinct. Include distinctive details; try to SHOW rather than simply TELL about someone. Include one tag or crowning detail that the reader will associate with them.

Most writers have little trouble with the ‘telling side’ of characterization. They quickly and easily sum someone up: he is a grump; she’s an entertainer. But writers often have a much harder time of explaining why they formed that opinion of the person. As a result, they don’t know how to demonstrate the truth of that assessment to the reader. Here are some ideas of what to look for in a direct or ‘showing’ approach to character sketches:

SHOWING CHARACTER

–APPEARANCE – What do they look like? What size, color, shape, weight is person? What kind of clothes do they wear? Do they have a narrow face, or a round, cherubic face? Green eyes or brown eyes? Do they wear a smile or a frown?

–MANNER – How do they move, walk, sit? What’s they’re posture like? How do they smoke a cigarette? Vape? Drive a car? Eat an ice cream cone?

–SPEECH – What do they say? How do they say it? Do they have a distinct dialect? How can you use this to characterize them? Is their speech individuated? How can you capture this?

–CHARACTER IN ACTION – How do they behave in their work, social and family life? What do their actions tell us about who they are? This is an especially effective way of characterization. Follow someone around work or at home. Record details of speech, manner, etc. See how they interact with other people.

We’ll discuss character sketches in my spring class, The Nature of Narrative. Let me know if you’d like to sign up!

In organizing a piece, narrative writers tell the story in terms of scenes linked chronologically, creating interest and suspense, pulling the reader forward through the story. Commentary, explanation and description can be added to the scenes or placed around them as long as they don’t detract from the narrative momentum, or profluence, as John Gardner referred to it in The Art of Fiction. Such stories have a beginning, middle and end, although not necessarily in that order. They arise out of a conflict that is resolved by the end of the piece.

Good story ideas for narrative writing meet the following criteria:

1) BASED ON SCENE – Organized around one or more scenes. Unlike a feature story, these pieces should be composed almost entirely of scenes. There can be passages of narrative summary that provide background information, but these should be incorporated into or around the scene.

2) EMPHASIZE CHARACTER – Elucidation of character lies at heart of these stories. They can convey information, but this should be done through the personalities central to the story.

3) ENCOURAGE CURIOSITY – Writers should appeal to readers’ curiosity, pulling them along with suspenseful storytelling, not letting them go until the end.

4) CONFLICT AND RESOLUTION FORMAT – The story has to be organized around a conflict, whether an external one like climbing a mountain, or an internal one of overcoming stuttering. Most of the best stories have a conflict that embraces both the internal and the external. Example: John has to overcome his fear to climb the mountain. Melissa meets a supportive speech therapist who helps her speak normally.

For more on story ideas, consider signing up for my spring writing class, The Nature of Narrative.

Scenic writing is the basis for some of the most moving, satisfying, sophisticated works of literature. It is especially effective in bringing readers into the story because it helps them create a world, a world that you the writer have inhabited and can share with the reader through words. Scenes present a visual, sensual world the reader can inhabit, a kind of imaginary garden with real toads, whether that’s the world of the astronaut program of Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, the vast landscapes of the Southwest in the work of Terry Tempest Williams, or the hard-bitten, humorous Irish Catholic childhood of memoirist Frank McCourt or the gripping nonfiction books of Pulitzer Prize winner Lawrence Wright, pictured below.

1) SETTING THE SCENE

This transition usually leads to a nut graph, a paragraph that suggests or explains the larger point or goal of the scene and furnishes its larger context. It’s called a nut graph because it puts all of these things together in a nutshell. Who? What? When? Where? And most importantly, why? As in, why should the reader care? What will the scene accomplish?

For more on how to set a scene, please sign up for my winter narrative and Seattle writing class, The Arc of the Story.

Go to the library or bookstores or magazine shop and begin reading publications. Some writers wouldn’t deign to do this, but it makes all the difference. What kinds of places publish profiles of political figures? Should you send your piece about airport security to an airline magazine or a travel magazine? How do you choose which outdoor magazine to contact about a mountain biking story? Reading the publications will help you answer these questions. Magazines and newspapers have distinct personalities, almost like people. Writers need to get to know them and then the questions of where to send a story soon becomes clear.

If you don’t take time to do this, you’ll be wasting time and money. Every newspaper or magazine occupies a certain market niche, serves a particular audience and is looking for a specific kind of story. For example, don’t bother pitching a story on a national political issue to your hometown newspaper unless there is a local angle.

Get to know the publication. Visit the publication’s website for writer’s guidelines; most publications will furnish these free of charge. Then read the magazine thoroughly, look at the ads, the letters to the editor. What kind of audience are they aiming at? Socially conscious? Upwardly mobile? Cigar Aficionado will not want your story on the evils of second-hand smoke but Mother Jones might pick it up.

What’s the style of the magazine? Straight reporting? Satire? Political commentary? Are the stories long or short? Are they mostly staff-written or written by freelancers?

What part of the magazine is easiest to break into? Many magazines include a front section of short profiles, often written by freelancers. Newspapers often publish reviews of books, restaurant s, concerts that are written by freelancers. Scope out the publication to figure out which department you’ll target for your query. We’ll discuss all this in more detail in my fall Narrative Writing Class, Tell Your Story, for The Writer’s Workshop.

Mike Medberry, author of Living in a Broken West: Essays, talked to my spring narrative writing class for The Writer’s Workshop about how to self publish a book. All those interested in deciding if and how to self publish their book will benefit from this talk. I’ve include the summary of it below.

By Mike Medberry

Henry David Thoreau who self-published the American classic, Walden, wrote that if you have built castles in the air, all of that work need not be lost as that is where your castles should be. He added, “Now put foundations under them!” You’ve written an interesting book at with extreme effort, and you’d like to sell it, so put a foundation under it! Do some research, take a critical look at your own writing, and a define how much self-publishing will cost and yield. The following are a few of the things that you might want to consider:

1) Define what you expect in publishing your own book. Is it for your friends or colleagues or do you think that your book serves a much broader audience? Your next steps will depend on that decision. Keep in mind that about 800 million books are published every year in the US, half of them self-published, and they sell only a handful of copies. Average book sales per year (standard publishers and self-published) are 200 copies and less than 1,000 copies in that book’s lifetime. Can you do better?

2) Build a foundation for your work: create a good website for $500 – 2500, develop high numbers of supporters on your defined social media networks like Facebook or Twitter, write supportive blogs on the web or articles in hard copy magazines or newspapers. This is all so basic but people often fail to accomplish it because it is hard, consistent, long term work.

3) Have your manuscript edited and understand what editing means. Good editors are expensive at $20 to $100/hour, but they are indispensable. There are essentially five kinds of editing: a) Developmental Editing which looks at the basic content of the manuscript; b) Structural Editing which looks at the logical flow of the manuscript, style, tone, and overall quality of your writing; c) Copy Editing which assesses the tone, reads for clear and consistent style, asks who is your audience, and looks at word choices and grammar; d) Line Editors should go through your writing line-by-line to look closely at the impact of your writing, word choices, and add polish that will allow your writing to be clear and eloquent; e) Finish Editing is the last stage of writing which focuses on raking up all of the missed minor errors like capitalizations, misspellings, word choice–things like using “there” when you meant to use “they’re” or “their.” All of this is pretty painful, but get used to that pain.

4) Design your book! I know, I know: it was news to me that I had to think about a million arcane details to make my manuscript look like a classy book. But, of course, I wanted my book to look like one of the very best! This should be a fun process, but you can get bogged down in accomplishing the many details to the point of its becoming numbing. I could always hire a consultant to iron out the particulars, but I would learn nothing. I found it very fascinating to learn. I suggest that you hire a good designer at roughly $2,000 to $5,000, retain many of the critical details, and work closely with her. Learn what she is doing for you. It is a lot! I will simply list the items: Define your book cover. Approve of the text, graphics, Table of Contents, and chapters. Place photos and write the captions. Create a publication page: define the International Standard Book Numbers or ISBNS, barcodes (which set the price of your book), QR codes all of which are available through the mystical company Bowker, which, it turns out, you must use. The publication page also includes acknowledgements, the author, credits, and defines the critical subjects that bookstores depend upon to create a shelf your book fits into, like adventure, memoir, or outdoor recreation. Inside the back cover includes your vita, photo of yourself, and defines your other publications. The outside of the back cover includes your picture, a great summary of your book, great quotes from recognized authors supporting your book, the logo for your publisher, the QR code, and the barcode. That is all you need… But the bookstores will know exactly what is needed!

5) Print the book and publish your book. Nowadays, it is much simpler, much cheaper, and more effective to print books than it was ten years ago because of self-publishing software and Print on Demand services. It is your decision to have your book printed in exactly the way that you’ve imagined and there is no stigma about publishing your own book, as there was in the past. Using color or distributing photos across the book or making editorial opinions are decisions that can be made by you and are now relatively cheap.

6) Find Target Audience – I think that self-publishers, you or me, can effectively aim at smaller audiences than standard publishers can and still make money; that is strictly a matter of your expenses and theirs, in which you are able to saturate your target at a more local place and at a reasonable price.

7) Choose publishing platform – Publishers include Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing and IngramSpark among many others, but in my world those two are absolutely key to consider. If your manuscript is in good shape, there will be no problem publishing your book with either or both publishers. If the manuscript is in bad shape, well, good luck… Read the contracts carefully or your book may be pulled from publication if you don’t follow their guidelines. You will come to understand that: Profit with Ingram = book price – 30% – printing price And that will set the price you can choose.

8) KDP vs Ingram – There are significant differences between KDP and Ingram, however. All independent bookstores will reject KDP books (or will offer you a consignment plan) and will favor Ingram because Ingram will guarantee that bookstores can return any book. That will cost you money, but you will have many more places to sell (all of the indie bookstores!) if you’re using Ingram. With the e-books the circumstances will reverse, however. It is a yin-yang relationship with publishers; you need both, and you must read that annoying contract very, very carefully with any publisher.

9) Distribute and sell your book. Your foundation and all the work you’ve done to publicize your book will come into play when you go to distribute and sell your book. With an action plan that extends one-year from the publication date you would be able to rack what is happening with your book and will help you plan readings. Keep good track of your book sales for tax purposes. This is particularly important when a store offers you a consignment plan, which will be hard to collect-on without good records.

10) Road to Success – Now, as if all of that wasn’t enough to think about, I’d say that you are on the road to a most extravagant and interesting success! And all of us should cheer for every other writer who treads upon this path.

Living in the Broken West: Essays:

SUMMARY SCENE OPENINGS – WRITING PROCEDURE

COPYRIGHT THE WRITER’S WORKSHOP

Scenic writing is the basis for some of the most moving, satisfying, sophisticated works of literature. It is especially effective in bringing readers into the story because it helps them create a world, a world that you the writer have inhabited and can share with the reader through words. Scenes present a visual, sensual world the reader can inhabit, a kind of imaginary garden with real toads, whether that’s the world of the astronaut program of Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, the vast landscapes of the Southwest in the work of Terry Tempest Williams, or the hard-bitten, humorous Irish Catholic childhood of memoirist Frank McCourt or the travel stories of V.S. Naipaul.

1) SETTING THE SCENE

This transition usually leads to a nut graph, a paragraph that suggests or explains the larger point or goal of the scene and furnishes its larger context. It’s called a nut graph because it puts all of these things together in a nutshell. Who? What? When? Where? And most importantly, why? As in, why should the reader care? What will the scene accomplish?

For more on how to set a scene, please sign up for my winter narrative and Seattle writing class, Follow the Story.

How to Promote Your Book

Promoting a book is not often an author’s favorite past time, but it can reap huge dividends in exposure and book sales. Molly Woolbright, the publicist at Sasquatch Books, visited my summer Seattle writing class, Writing Your Story, to provide insight into the process.

“I will broadly describe how a publicist at a traditional publisher approaches a book’s campaign and hopefully demystify the process,” she explained.

Woolbright emphasized that digital marketing has taken on new importance in a time of social distancing. In the past, book tours and talks made up a significant part of the marketing plan. With those options limited , other strategies need to be developed, including talks and meetings via Zoom and other web conferences.

She detailed a number of effective ways of getting the word out about your book. I’ll include the highlights of her talk to my Seattle writing class, Writing Your Story, below:

Overview of Book Publicity

An in-house publicist at a traditional publisher works on a variety of books at a time, striving to secure a mix of trade reviews and regional and national media for each. From the general public’s perspective, a book campaign is typically about 3 months long; from an author and publisher’s perspective, the work begins at least 6 months before a book is published.

Long-Lead Media

About 6-8 months out from publication

Advance reader copies (otherwise known as ARCs or galleys) sent to media outlets that work far in advance, including: Print magazines, Trade journals (Publishers Weekly, Library Journal, Booklist, etc.), Podcasts.

Short-Lead Media

About 1-2 months out from publication

Finished copies sent to media outlets that work on a shorter timeframe, including: Newspapers, radio, TV, blogs.

Local/Regional Media

Often overlooked in favor of bigger or more prestigious national media outlets, your local newspaper, magazines, blogs, radio, and TV stations are a great starting point to build buzz (while still striving for national hits). The Amazon algorithm is fed by any and all publicity, and local media is more likely to take notice.

Optimizing Your Author Platform for Media

Book promotion, regardless of genre, is often more about the author than the book—it’s about you and the expertise you can provide or discussions you can spark. Whether you’re working with an in-house publicist or you’ve hired a freelancer, one of the most helpful steps you can take to assist her efforts in securing media is to boost your online presence.

Website

From a publicity perspective, a website is the most useful asset you can have as an author. Whereas social media is ephemeral, a website offers a consistent representation of you and your work. Think of it like a toolbox where journalists/reviewers/editors can go to find more info.

For more on book promotion and writing technique, please consider signing up for my next Seattle writing class, online writing class or travel writing class through www.thewritersworkshop.net.

Reviewed by Kate Jackson

The Queen’s Gambit is an opening move in chess used by the player of the white pieces. The objective of the move is to temporarily sacrifice a pawn to gain control of the center of the board. The book by Walter Tevis of the same name chronicles the journey of a young chess prodigy as she becomes the center of the fictional world of competitive chess in the 1960’s. The title is emblematic of the personal sacrifice required by the intensity of competitive chess at the highest level.

Loneliness, genius, and obsession are at the core of this portrait of Beth Harmon who loses her mother at the age of eight and is taken to the Methuen Home for orphans. There she discovers an affinity for the tranquilizers supplied daily by the school and a love for the game of chess. She learns chess by watching and by playing against the school janitor, Mr. Shaibel, who recognizes her talent and introduces her to competitive chess. Her only friend and mentor at the home is Jolene, an older black girl who assumes a pivotal role later in Beth’s life. Their dialogues provide a window into issues about race and privilege relevant then and now.

At the age of 13, Beth is adopted by a couple who soon separate. She is mothered by Mrs. Wheatley, a lonely woman with her own addiction, in this case, to alcohol. At school, Beth is an outsider with little connection to her peers. Her gift for playing chess offers another life as she begins to win at state and regional tournaments. Her mother realizes the potential for money and travel offered by these competitions and revels in the celebrity status Beth achieves due both to her age and gender in a game dominated by males.

Beth’s story illuminates the utter discipline and commitment it takes to become a chess champion. She lives in virtual bubble dominated by studying, thinking about, and constantly playing chess. Devotees of chess will appreciate the discussion of classic moves and strategies taken from actual games.

If you watched the Netflix miniseries based on the book, you may wonder why you would want to read the book. Yes, the story is basically the same with some significant changes in the film adaptation. But the written version skillfully develops the inner voice of the main character and suggests that the gift of genius comes at a heavy price.

By Kate Jackson

Two fathers, two daughters, Israeli and Palestinian, woven together by two tragedies: this is the substance of Colum McCann’s latest novel. Published in February 2020, the characters and events are based on actual people and events. The word, apeirogon, means “a shape with a countably infinite number of sides.”

The novel begins with Rami, an Israeli man on a motorbike, entering Palestinian territory. His yellow license plate signals his nationality to the border guards. The reader is immediately brought into the divided world where Palestinians and Israelis live separated by walls, barbed wire, barricades and checkpoints. Only the many species of birds, occasional characters in the book, have freedom of movement.

Soon we are introduced to Bassam. He has a distinctive limp as a result of childhood polio. He has a broken heart as a result of the untimely death of his ten-year-old daughter, Abir. She was near her school when she was shot in the back of her head with a rubber bullet.

Midway into the novel, Rami and Bassam meet. They join a Parents Circle. By then, we know their respective stories and the anguish both experienced when their children were taken from them. Rami’s fourteen-year-old daughter, Smadar, died in an explosion set off by Palestinian suicide bombers near a café ten years before Abir died at the hands of an Israeli soldier.

Both fathers have ample reason for bitterness and enmity but over the course of the narrative, form a strong bond of friendship and support. Together and separately, they travel outside their borders to tell their daughters’ stories and confront the futility of violence while demonstrating a way towards healing deep wounds.

As the title suggests, this is a multifaceted tale. It explores the depth of human pain and loss that transcends nationality and time. It reveals the results of policies set by the rulers over the ruled who have no political voice. It is a story of ancient cultures so close in proximity and history and so far apart in attitude. It is the story of two men who found voices to spread messages of peace and hope born out of tragedy.

The book is written with 1,001 sections, some only a sentence or two long and others with many paragraphs. The narrative travels back and forth in time, place and character. It seems repetitious at times. But it is a powerful and unconventional story of and for our times.

The Writer’s Workshop Book Review is published by The Writer’s Workshop. Let us know what you think and if you’d like to contribute a review. We review books of narrative fiction and nonfiction. Please be in touch!