In my Seattle writing courses, I tell students that once upon a time, writers would send out manuscripts to traditional publishers until they got a contract. If they tried and tried but got no contract, some of them would send the manuscript to what was called a vanity press, a company that published the book for payment by the author. Such “vanity” books had little cachet or influence and often promptly disappeared, though it must be noted that Henry David Thoreau’s Walden was first published in this manner and has sold thousands of copies. Most of these titles however disappeared without much of a trace.

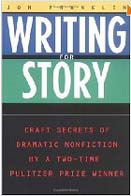

Now, with the advent of Amazon’s CreateSpace and other publishing tools, the world of self-publishing is gaining new cachet. For this reason, I invited Emilie Sandoz-Voyer of Girl Friday Productions to speak about the latest trends in self-publishing for my Seattle writing course, Writing for Story.

“I shepherd authors through the editorial and publishing process,” she said. “Self publishing is my bread and butter. What does it mean to be a self published author? It means you are the publisher, writer, editor and producer, uploading your title to be available on Amazon and other places. You’re a publishing entrepreneur. It can be overwhelming at first, but there are resources available and it’s become easier to self publish your book.”

Sandoz-Voyer emphasized you have to think like a publisher if you choose the self-published option. Who will buy your book? How will you get copies to them?

“Amazon’s CreateSpace service books will ship via Amazon, a great option for self published authors.” she said. “You can also go through Ingram Spark or Lightning source. You can go through more than one channel. You’re the publisher, not the distributor, and you keep all your royalties.”

Keeping all your royalties sounds very appealing. What’s not so appealing is doing everything a publisher does to come up with a professional quality book. Writing the book is just one aspect of this, as I remind students in my Seattle writing course.

“I highly recommend hiring editors to polish that prose, so it looks professional,” said Sandoz-Voyer. “Hire a cover designer to make your book stand out.”

The Writer's Workshop

The Writer's Workshop